Leadership, Accountability and Your Organization’s Risk Profile

Recent media attention has cast light on the unusual number of aviation system-related accidents, incidents and near-misses that have plagued our industry over the past several months. While we continue to hear pundits and media personalities alike remind us how safe aviation is, we cannot be blinded by these statements nor take them as absolutes. As aviation safety professionals, we know that our system is fallible whenever it involves people or technology. If you want absolute safety in aviation, it is 1G and zero airspeed and walk away very carefully.

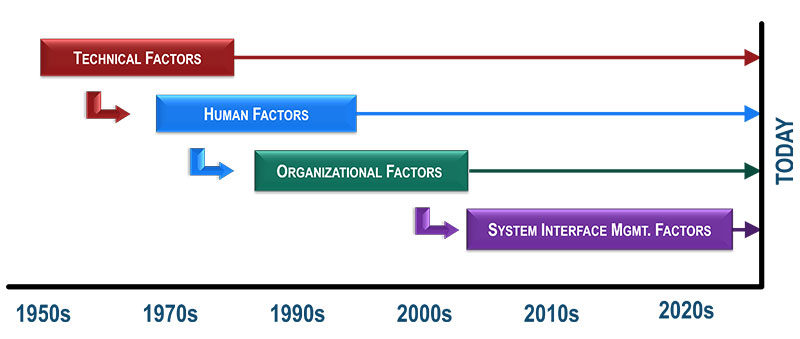

Since the dawn of aviation, we have faced and addressed risk in all its iterations—from technical anomalies, human performance and organizational issues, to system interface management factors in today’s operational environment.

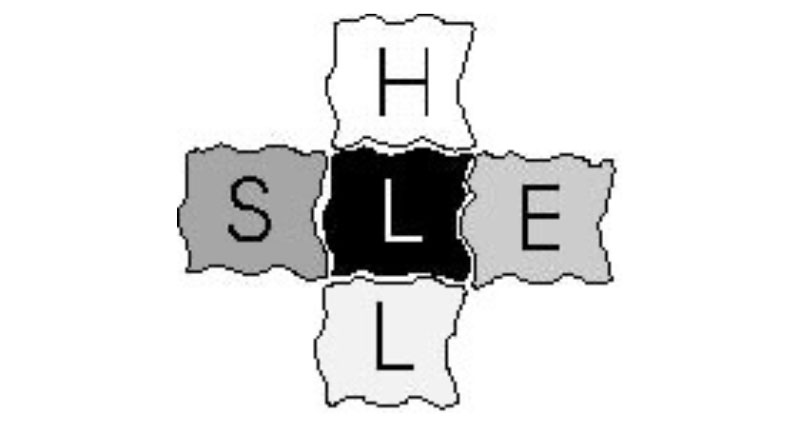

Taking a page from ICAO Document 9859, Safety Management Manual, the introduction of the SHELL model is used to illuminate the critical components discussed within this article.

The SHELL model1 as a concept has its genesis in the understanding of the interaction between people and systems. The acronym stands for Software (the rules, procedures and written documents), Hardware (air traffic control, communication systems, controls and surfaces, displays and functional systems), Environment, Liveware (humans) and, by extension, a second Liveware (the person-to-person interface).

The goal of the SHELL model is to illuminate how incongruent relationships between humans and systems can be identified proactively, preventing an accident or negative consequence. At worst, problems can be identified reactively, because of an accident or negative consequence and the subsequent investigation, if performed properly (a subject for another day)!

So, while this may seem straightforward and obvious, let’s delve a little deeper by going beyond the obvious human factors (HF) often associated with Livewire and embroidering HFACS, the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System model as developed by Dr. Scott Shappell and Dr. Doug Wiegmann.

Here, we are looking at the active and latent failure modes that can occur within the envelope of the SHELL components.

Understanding Perception Errors

From an organizational perspective, recent events reflect “perception errors” based on the functionality or interface management, or lack thereof, of an installed system or program. For example, an organization’s manual system, such as its operational manuals (GOM, FOM, GMM, etc.), may dictate certain policies, procedures and processes, which, if followed and applied correctly within the SHELL environment, will reduce risk to a level accepted by the organization and by default, the regulatory body overseeing that operational environment.

Now, adding support systems, such as the safety management system (SMS), is sometimes required by regulation for 14 CFR Part 121 Air Carriers and certain 14 CFR Part 139 Airports. In others, it is not mandated but suggested for 14 CFR Part 135, Part 125, Part 91 operations. In still other areas like public use (think police and fire services), it is not required at all, and only the more enlightened public use operators have embraced these “best practices” as voluntary standards to reduce risk to as low as reasonably practicable.

As the cornerstone of any documented SMS, understanding and comprehending risk assessment is vital to using the tools and support software to their fullest.

Over the course of the past several years, a wide disparity has emerged with the advent of various software solutions that “guide” operators through the process. Regrettably, many operators have purchased the manual or the software and assume that because they own it, it must be effective. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

The fact is, if the full process is not utilized thoughtfully, the outcome will, in most cases, be inaccurate or inconclusive, providing limited insight and understanding of the associated risks surrounding an event and how best to mitigate them.

We are diluting the effectiveness of some of our most critical programs by ineffectually adding a software or audit tool that, for a variety of reasons, only skims the surface. It touches only the most obvious information, not delving deep enough because the organization lacks effective onboarding training for a new system, full understanding of the system’s power or availability of sufficient resources and time to do the work.

We are doing a disservice to our industry and the trust of the traveling public by diluting our efforts to understand the risk profile and all its influencers (S-H-E-L-L) fully.

The Bottom Line to an Effective, Compliant Governance/Safety Management System

Advancing the safety culture within any organization requires leadership’s awareness and deep understanding of the actual elements of the SMS rather than just becoming familiar with the words on the page or implementing its outward manifestations. True commitment—living it day by day as a core component of the organization’s corporate culture and vocabulary and holding the management structure accountable—is the key to success.

Safety can’t be delegated—it MUST live and thrive within the day-to-day actions of senior and functional leadership—your words, your actions, every day at every level of the organization, within each business unit, department and silo. This sets the tone for sound interface management, engaged supervision and procedural adherence.

Organizations cannot afford to rely on regulations alone, and this is more relevant today than ever. These are the minimum standards. The expectation and duty of care are no longer acceptable at such a low level.

What we do above and beyond the regulations, such as embracing an SMS when required to (e.g., Part 121) or voluntarily (e.g., Part 91, Part 135) as a best practice, and applying a maturity assessment to evaluate your SMS’s performance when viewed against the complexity of your operation and risk profile, enables the determination of actual effectiveness beyond mere compliance.

References:

1 First developed by Elwyn Edwards in 1972, with a modified diagram to illustrate the model developed by Frank Hawkins in 1975.

ICAO Document 9859, Safety Management Manual

Skybrary.aero

AvMaSSI provides safety, security and operational integrity evaluations, consulting and auditing to airlines, airports, charter and corporate operators, OEMs, marine operators, seaports, governments, international agencies and financial institutions the world over. AvMaSSI provides IS-BAO and IS-BAH preparation and audit services and supports Global Aerospace and its SM4 and Vista Elite Programs with focused safety/SMS, security, regulatory compliance and IS-BAO auditing services. AvMaSSI is a proud member of the Global Aerospace SM4 partnership program.

http://www.Avmassi.com

© 2025 Aviation & Marine Safety Solutions International. All Rights Reserved.

Next ArticleRelated Posts

Part 108: The Next Step in BVLOS Integration and Drone Innovation

As the drone industry awaits the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) forthcoming Part 108 regulations, the landscape of Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations stands on the brink of transformation. These anticipated rules aim to standardize BVLOS flights, enabling more complex and expansive drone missions across various sectors.

Giving the Hazard Log the Attention It Deserves

Safety risk profile. Hazard log. Hazard risk register. Whatever you call it internally, one thing is clear: It is a fundamental requirement in your safety management system.