Developing Escalation Thresholds for Emergencies

Your view on what constitutes an emergency is significantly shaped by your education, training, life and career experience and by the scope of your responsibilities and job functions.

As a company that monitors over 150,000 flight operations per year and provides emergency services to nearly 200 organizations, we’ve been exposed to a wide variety of situations that one could classify as an emergency. We’ve learned that events that trigger a full-scope emergency response at one organization might be viewed as “just another day at the office” at another. Further, the reaction to that same event by different departments within the same company might be vastly different.

A few recent examples come to mind:

Following a return-to-field we identified on a client’s aircraft shortly after they departed a busy international hub, our call to the company’s chief pilot was met by the dismissive comment, “[popular flight tracking website] says they haven’t departed yet.” A few minutes later, a subsequent call to the company’s flight logistics team yielded a decidedly more nervous response and an immediate request that we investigate further.

After a few phone calls and a review of air traffic control recordings, we confirmed that the aircraft had departed and immediately returned to the field due to a bird strike that forced a left engine shutdown. This aircraft was used for scheduled service with dozens of passengers onboard, all of whom needed to be re-accommodated on another flight.

A few weeks before that event, we contacted a client’s dispatch team regarding a diversion on one of their company aircraft. The dispatcher we spoke with advised that the diversion was due to “some sort of mechanical indication” and seemed significantly unconcerned.

We continued to monitor the flight closely and observed the crew go missed on their first approach to their new destination, maneuver southwest of the field for several minutes, and then conduct a second approach which appeared to be successful. We received a frantic call from the operator’s director of safety a few minutes later, advising that the crew had reported severe flight control issues, had to fight to maintain control of the aircraft and nearly struck a wingtip on the runway on their first attempted landing. The director later shared that this was the closest their company had come to experiencing an accident in their 20+ years of operation.

In both cases, had the outcome been just one order of magnitude worse, the repercussions for the operators could have been significant. Their emergency response teams would be significantly delayed in assembling and responding, death or injury notifications of family members would be postponed, their communications team would be poorly prepared for social and news media coverage headed their way and essential timelines such as NTSB reporting could be missed.

Defining “Emergency”

To mitigate similar discrepant responses within your organization, it may be helpful to sit down with each of your departments and ask them to share examples of different situations your organization might encounter that they would view as an emergency, why they view them as such and what the consequences would be for their department. As you review your notes following this meeting, develop a consolidated list of situations that A) are viewed as an emergency across all departments and B) perhaps aren’t viewed as equally across the board but would constitute a particularly severe emergency for a specific department.

Following this exercise, we suggest developing a simple “escalation matrix” that you can distribute to your team for reference. This matrix consists of a short list or table with different sample scenarios and guidance on how to respond to each.

When developing this matrix, include examples of scenarios that are realistic for your operation, and focus the instructions on immediate steps for responding, rather than long-term actions. Leave the detailed forms, checklists and guidance for your Emergency Response Plan (ERP), and focus on creating a reference that is simple enough it can be committed to memory. The primary goal of your escalation matrix should be to encourage your team to activate your full ERP whenever appropriate, so they can avail themselves of the tools and resources contained therein.

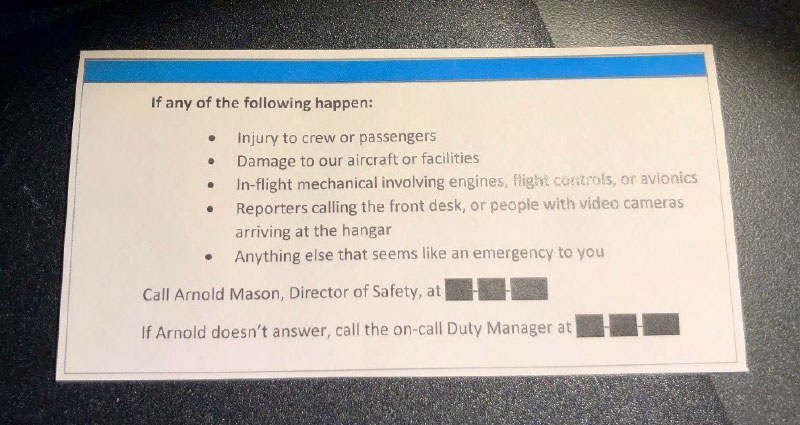

Ideally, this matrix would be concise enough to be printed on the back of an ID card, saved in a note on an employee’s phone or written on an index card taped next to a computer monitor for easy reference. With today’s pace of operations, your stressed and busy colleagues are more likely to follow a short procedure they can easily find, understand and remember than a more complex one contained deep within a manual or application they don’t use every day.

Here is an example of a simple escalation matrix one of our clients is using:

Training on Your Escalation Matrix

Once you’ve developed a matrix tailored to your operations, train on it. This reference and your associated procedures are a great topic to review with your team once a quarter, separately from your more comprehensive ERP drills. Between these reviews, a suggestion to help maintain “currency” is to conduct frequent spot checks, which can be as simple as stopping by a colleague’s office and asking “If XYZ happened, would you escalate it or not?”

Most importantly, take advantage of any events that do happen as an opportunity to learn and to improve your matrix. Encourage your team when situations are handled appropriately, coach them when they aren’t and adjust your procedures as needed.

Finally, we’ve found it best to establish and teach a policy of, “If you aren’t sure, just escalate it.” It’s always easier to over-respond and then realize you can stand your response team down than it is to play catch-up hours later or deal with the fallout from something that could have been mitigated if the right people were notified earlier in the process.

A common failure point we see in our clients’ response to ERP-activating events is that their ERP simply wasn’t activated. All of the checklists, procedures and tools you’ve spent years developing, testing and fine-tuning as part of your response program are useless if your ERP remains on the proverbial “dusty shelf” when you have an actual emergency. A simple “escalation matrix” may be just the ticket you need to avoid this pitfall.

Fireside Partners, Inc., is a fully integrated emergency services provider designed to provide all services and resources required to respond effectively and compassionately in a crisis situation. Dedicated to building world-class emergency response programs (ERP), Fireside instills confidence, resiliency and readiness for high-net worth and high-visibility individuals and businesses. Fireside provides a broad array of services focused on prevention and on-site support to help customers protect their most important assets: their people and their good name.

http://www.firesideteam.com/

© 2025 Fireside Partners Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Next ArticleRelated Posts

Part 108: The Next Step in BVLOS Integration and Drone Innovation

As the drone industry awaits the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) forthcoming Part 108 regulations, the landscape of Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations stands on the brink of transformation. These anticipated rules aim to standardize BVLOS flights, enabling more complex and expansive drone missions across various sectors.

Giving the Hazard Log the Attention It Deserves

Safety risk profile. Hazard log. Hazard risk register. Whatever you call it internally, one thing is clear: It is a fundamental requirement in your safety management system.